The history of Buddhism begins in the 6th century BCE in and around the ancient Kingdom of Magadha in northeastern India. Spreading from India to Central and Southeast Asia, China, Korea, and Japan, Buddhism has played a central role in the spiritual, cultural, and social life of Asia. During the 20th century Buddhism spread to Europe and the United States with more than 470 million followers practicing different traditions around the world. This lesson will provide a brief history of Buddhism which includes significant people and events, address the relationship between Buddhism and non-Buddhist communities, and introduce how significant people and events in Buddhist history contribute to Buddhist identity, culture and religious practice.

Objectives

- identify people and events significant to Buddhist history

- describe the historical relationship between Buddhist and non-Buddhist communities

- explain how significant people and events in Buddhist history contribute to Buddhist identity, culture and religious practice.

Pre-Buddhist India

Buddhism arose in northeastern India sometime between the late 6th century and the early 4th century BCE, during a period of social instability characterized by the breakdown of tribal unity and growing discontent with Hindu practice of sacrifice and ritual by the priestly Brahman class in Hindu society. A series of ascetic movements based on self-discipline and abstention aimed to create more personal and spiritual religious experiences than those found in the Vedas (Hindu sacred scriptures). The literature that grew out of this movement, the Upanishads, offered a new emphasis on renunciation and transcendental knowledge. As a result, many new sects emerged in northeastern India which was less influenced by Vedic tradition, and these sects included a variety of diverse approaches such as skeptics, atomists, materialists, antinomians, and proto-Samkhya groups. Yet, the most important sects to arise at the time of the Buddha were the Ajivikas who emphasized the rule of fate (niyati) and the Jains who stressed the need to free the soul from matter. Jainism influenced the development of Buddhism; the two religions share many features, terminology and ethical principles, but emphasize them differently.

Buddhism, like many of the sects that developed in northeastern India at the time, was comprised of three components; a charismatic teacher as leader, the teachings of the leader, and a community of supporters. In the case of Buddhism, this pattern is reflected in what is known as the Triratna, or “Three Jewels”; Buddha (the teacher), dharma (the teaching), and sangha (the community). Since its beginnings in India, Buddhism has accepted both men and women of any race, social class, or caste. Many contemporary Buddhist communities continue to use the triratna as a symbol today, and many Buddhist ceremonies include the Threefold Refuge declaration to ‘take refuge’ in the three jewels.

The Budda

The first teacher, and recognized founder of Buddhism is Siddhartha Gautama, who was born into a wealthy family in what is present-day Nepal on the northern edge of the Ganges river basin. The precise dates of his life are debated between the mid-6th to mid-4th centuries BCE. Information about his life comes largely from Buddhist texts, the earliest of which were produced shortly before the beginning of the Common Era several centuries after his death.

Tradition narrates that Gautama was born into the ruling Shakya clan and was a member of the Kshatriya, or warrior, caste. His mother, Maha Maya, dreamt one night that an elephant entered her womb, and 10 lunar months later, while she was strolling in the garden of Lumbini, her son emerged from under her right arm. As a wealthy prince, he married at 16, had a son, and while venturing ventured outside the confines of his family property at 29 years of age, he observed the suffering of those who were less fortunate than he was. He decided to reject his life of riches, and he spent the next six years leading an ascetic lifestyle practicing meditation with several teachers and five companions. While bathing in a river, however, he fainted from weakness and thereby concluded that deprivation was not the path to liberation from suffering. He promoted the idea of the Middle Way, which refers to moderating between two extremes of indulgence and deprivation. Buddhists believe that after 49 consecutive days of meditation under a Bodhi tree, Gautama received the Four Noble Truths and the Eight Fold Path which provide the foundation for Buddhist philosophy. He made this announcement in public and eventually acquired a group of disciples. His followers referred to him as the Buddha, meaning the Enlightened One, which was an ancient Indian title which referred to an enlightened being who has awakened from the sleep of ignorance and achieved freedom from suffering. He spent the next 45 years traveling throughout northeastern India with his disciples teaching his message, establishing orders of monks and nuns, and receiving the patronage of kings and merchants. Before he died at the age of 80, he met with his disciples to impart his final instructions and passed into nirvana, known as liberation from the lifecycle. His body was cremated and relics were distributed and enshrined in stupas (funerary monuments that usually contained relics), where they are still venerated today.

According to the various traditions, buddhas have existed throughout history and will continue to exist in the future. Some Buddhists believe that there is only one buddha for each historical age, others that all beings will become buddhas because they possess the buddha nature (tathagatagarbha). In addition, there are others who are considered Arhats (worthy ones) and bodhisattvas (those who have dedicated themselves to achiebving enlightenment.) The first Buddha, Gautama, is referred to as Shakyamuni, which means ‘Sage of the Shakya Clan’. In Buddhist texts he is most commonly addressed as Bhagavat (often translated as “Lord”), and he refers to himself as the Tathagata, which can mean both “one who has thus come” and “one who has thus gone.”

After Gautama died, or entered into Nirvana (the highest state of liberation from the cycle of death and rebirth), his followers began to organize a religious movement and his teachings became the foundation for what would develop into Buddhism and the various Buddhist traditions practiced today.

The Buddhist Schism

Shakyamuni did not write down his teachings, and for several centuries following his death, his teachings were recited orally from memory. Different monks, bhikshus, memorized different portions and at early conferences of sangha members one of the most important tasks was to recite the teachings in their entirety. Over time, however, Buddhism split into two different directions.

The Theravada ( “Way of the Elders”) represented a conservative community that compiled versions of the Buddha’s teachings that had been preserved in collections called the Sutta Pitaka or tripitaka (three baskets) comprised of the Vinaya Pitaka (monastic rules), Sutras (discourses) and Abhidarma (systematic treatises). Theravada is dominant in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia.

The Mahayana (“Greater Vehicle”) has many texts in several languages including Chinese, Japanese and Tibetan with additional teachings integrated into the sutras which were considered authoritative because they made salvation available to more people. These teachings were purportedly made available by the Buddha to his more advanced disciples. Mahayana is dominant in East Asia and Vietnam.

A third tradition, Vajrayana (“Diamond Vehicle”), emerged 500 years later and it is considered by followers to be the culmination of the first two traditions. Also known as Esoteric Buddhism, it developed in China around 716 to 720 CE during the reign of emperor Xuanzong. Three ‘Great Enlightened Masters’, Śubhakarasiṃha, Vajrabodhi, and Amoghavajra arrived in Daxing Shansi (Great Propagating Goodness Temple), which was the predecessor of Temple of the Great Enlightener. Daxing Shansi was established in the ancient capital Chang’an, today’s Xi’an, and became one of the four great centers of scripture translation supported by the imperial court. Esoteric Buddhism integrated the prevailing teachings of China (Daoism and Confucianism) with Buddhism, and this developed the practice of the Esoteric school. Vajrayana is dominant in Tibet and the Himalayas.

Buddhism and Empire, Ashoka the Great

In the centuries following the Buddha’s death, the story of his life was remembered and embellished, his teachings were preserved and developed, and the community that he had established became a significant religious force. Many of the wandering ascetics who followed the Buddha settled in permanent monastic establishments and developed monastic rules. At the same time, the Buddhist laity came to include important members of the economic and political elite.

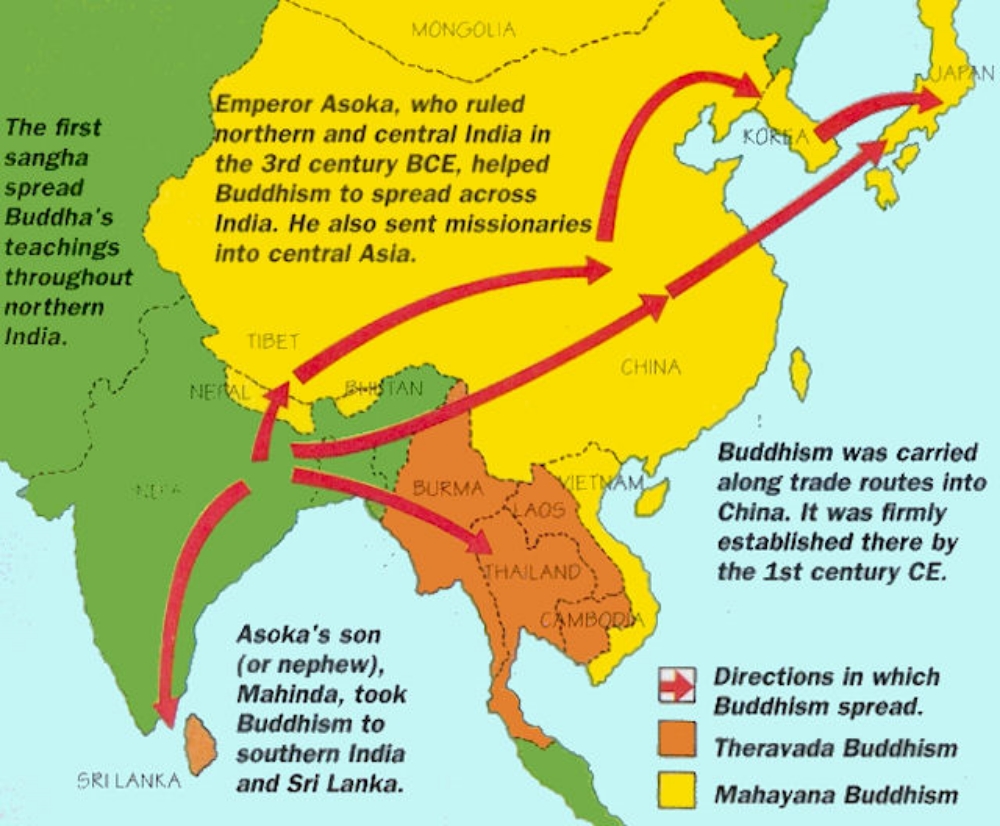

During its first century, Buddhism spread throughout much of northern India. According to Buddhist tradition, invitations to the Council of Vesali (Sanskrit: Vaishali) were sent to monks living throughout northern and central India. By the middle of the 3rd century BCE, Buddhism had gained the favor of a Mauryan king, Ashoka the Great, who had established an empire that extended from the Himalayas in the north to almost as far as Sri Lanka in the south. Ashoka made Buddhism the state religion of India. He built Buddhist monasteries and funded missionary work. Watch the video below to learn more about Ashoka’s role in expanding Buddhism.

Shunga Dynasty (2nd and 1st BCE)

The Shunga dynasty (185–73 BCE) emerged about 50 years after Ashoka’s death. Buddhist religious scriptures such as the Aśokāvadāna allege that Pushyamitra (an orthodox Brahmin) was hostile towards Buddhists and persecuted the Buddhist faith. Buddhists wrote that he “destroyed hundreds of monasteries and killed hundreds of thousands of innocent Monks”: 840,000 Buddhist stupas built by Ashoka were destroyed and 100 gold coins were offered for the head of each Buddhist monk. In the light of literary and archaeological evidence, historians claim that the end of Ashoka’s sponsorship led to a natural fall and there is no evidence of active persecution has been noted. During the Shunga dynasty, Buddhist monks left the Ganges valley.

Hellenization of Buddhism (2nd century BCE)

Greek expansion into the Indian continent by king Demetrius I established an Indo-Greek kingdom in parts of Northwest South Asia. Buddhism flourished, and the famous king Menander (160–135 BCE) is believed to have converted to Buddhism. Mahāyāna tradition presents him a great benefactors. Menander’s coins bore designs of an eight-spoked dharma wheel, a classic Buddhist symbol. It was during this time that Buddhism was hellenized. The first anthropomorphic, human-like, representations of the Buddha emerged in a realistic style known as Greco-Buddhist which includes Greek stylistic elements such as a toga-like wavy robe, the stance of the upright figures, Mediterranean curly hair and topknot, and the quality of the faces.

Watch the video below to view the syncretic relationship between Greek art and Buddhist representation in a style that continues to influence Buddhist art today

Kushan Empire (30-375 CE)

The Kushan empire was established by invading Yuezhi nomads, and eventually included most of northern India as well as Pakistan and Afghanistan. The Kushans also adopted elements of the Hellenistic culture of Bactria and the Indo-Greeks,and Gandharan Buddhism was a synthesis of Greco-Roman, Iranian and Indian elements. The Gandhāran Buddhist texts are the oldest Buddhist manuscripts. During this time, stupas and monasteries were built in the Gandhāran city of Peshawar with Kushan royal support, and a series of councils helped strengthen the Gandharanian tradition. After the Kushan empire fell to Hephthalite White Huns invaders in 440 BCE, Gandharan Buddhism continued to thrive.

The Kushan empire’s unification and support of Buddhism allowed it to easily spread along the trade routes throughout Central Asia. During the first century CE under the Kushans, the Sarvastivada school expanded, and some of the monks carried Mahayana teachings into areas such as modern-day Pakistan, Kashmir, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan. As Buddhism spread, monks began to translate and produce texts in local languages.

Gupta Empire (4th -6th century)

Buddhism continued to flourish in India during the Gupta Empire, and Gupta rulers supported and enlarged the Nālandā university, the largest and most influential Buddhist university in India for many centuries. (To learn more about Nalanda, click here.) The influence of the Gupta style of Buddhist art spread from south-east Asia to China, and during this period, Chinese pilgrims visited India to study Buddhism. One of the pilgrims is known as Faxian, a Buddhist monk and translator who traveled by foot from Ancient China to Ancient India, visiting many sacred Buddhist sites in Central Asia, the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia between 399-412. To learn about Faxian’s travels, watch the multi-part series of mini-docs below.

Pala Empire (8th -12th century)

The Pāla Empire emerged in the Bengal region in the 8th century. The Pālas built several significant Buddhist centers, such as Vikramashila, Somapura and Odantapuri, and they provided support for older centers like Nalanda and Bodh Gaya. At these centers, Buddhist scholars Atisha and Santaraksita elaborated on different philosophies as well as the study of linguistics, medicine, astronomy, music, painting, and sculpture. Under the Pālas, Mahāyāna Buddhism thus flourished and spread to Tibet, Bhutan and Sikkim.

A milestone in the decline of Indian Buddhism in the North occurred in 1193 when Turkic Islamic raiders burnt Nālandā. By the end of the 12th century, following the Islamic conquest of the Buddhist strongholds in Bihar and Bengal, and the loss of political support coupled with social pressures, the practice of Buddhism retreated to the Himalayan foothills in the North and Sri Lanka in the south. Additionally, the influence of Buddhism also waned due to Hinduism’s revival movements such as Advaita, and the rise of the bhakti movement.

Buddhism Enters China through the Silk Road

The international trade route known as the Silk Road not only carried goods between China, India, the Middle East and the Mediterranean world, it also transported new ideas, technologies and philosophies. Kingdoms in Central Asia played a key role in the transmission of Buddhism to China.

Buddhism flourished in the eastern part of central Asia. Indians and Iranians lived in major cities of this region like Kashgar and Khotan. The first translators of Buddhists scriptures into Chinese were Persian. The region produced a rich body of Buddhist works of art as well as Buddhist texts such as those found in Dunhuang. After the Zoroastrian Sassanian empire invaded the region in 226 CE, Buddhism continued to survive under the new regime. However, the Islamic conquest of the Iranian Plateau in the 7th century followed by the Muslim conquests of Afghanistan and the Ghaznavid kingdom in Central Asia led to the decline and eventual disappearance of Buddhism from this region. In China however, Chinese Buddhism or Han Buddhism, transformed Chinese culture in areas such as art, politics, literature, philosophy, medicine and material ways of living.

Han Buddhism (148 CE)

The first documented translation of Buddhist scriptures from various Indian languages into Chinese occurs in 148 CE with the arrival of the Parthian prince-turned-monk An Shigao who worked to establish Buddhist temples and organized the translation of Buddhist scriptures into Chinese. This launched the beginning of a wave of Central Asian Buddhist proselytism that was to last several centuries.

Mahāyāna Buddhism was first widely propagated in China by the Kushan monk Lokakṣema (164–186 CE), who came from the ancient Buddhist kingdom of Gandhāra. Lokakṣema translated important Mahāyāna sūtras, and these translations continue to give insight into the early period of Mahāyāna Buddhism. This corpus of texts emphasize ascetic practices, forest dwelling, and states of meditative concentration.

Buddhism and European Colonialism

During the 19th century, European intellectuals became aware of Buddhism during the European colonization of India and Asia. Colonial magistrates relied on local people to work as servants and administrators, and these professional relationships exposed Europeans to local ideas and belief systems. In addition, Christian missionaries working with colonial governments also learned about Buddhism from local people, and since Buddhism does not include deity worship and is considered more of a philosophy than a religion, it was not always considered an incompatible with the teachings of Christianity.

Sir Edwin Arnold’s book-length poem The Light of Asia (1879), which details the life of the Buddha, was a successful early publication on Buddhism that led to much interest among English-speaking middle classes. The work of western Buddhist scholars like Hermann Oldenberg (1854–1920), T. W. Rhys Davids (1843– 1922) and F. Max Müller was also influential in introducing Buddhism to a European audience.

In Continental Europe, interest in Buddhism increased during the late 20th century, with an exponential increase in Buddhist groups in countries like Germany. In France and Spain, Tibetan Buddhism has the largest following. In the UK, the Triratna Buddhist Community arose as a new modern Buddhist movement.

Buddhism and US Immigration

The Theosophical Society, an organization formed in the United States in 1875 by Helena Blavatsky to advance Theosophy ( a philosophy that a knowledge of God may be achieved through spiritual ecstasy, direct intuition, or special individual relations) was very influential in popularizing Asian religions in the United States.

The Chinese-Exclusion Act (a federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882 prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers) was repealed by the Magnuson Act in 1943. This act not only allowed people to enter the US from China, it also enabled Chinese culture and religion to enter into the United States. During the post World War II era, Buddhism was appropriated by the counter-cultural Beat Generation, and the work of D.T. Zuzuki (a Japanese author of books and essays on Buddhism, Zen (Chan) and Shin) became instrumental in spreading interest in both Zen and Shin (and Far Eastern philosophy in general) in the United States.

During the counter-cultural revolution in the US in the 1960s, Asian Buddhists such Hsüan Hua, Hakuun Yasutani and Thích Nhất Hạnh became very popular teaching Zen Buddhism to an American audience. Shunryu Suzuki opened the Soto San Francisco Zen Center in 1961 and the Tassajara Monastery in 1967. During the Vietnam war, refugees from Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia began immigrating to the US in 1975. Theravada vipassana meditation was also established in the West, through the founding of institutions like the Insight Meditation Society in 1975. The Tibetan diaspora also spread Tibetan Buddhism into the United States with all four major Tibetan Buddhist schools represented in the US with approximately ten to twenty million adherents. To learn more about Buddhism in America, visit the Pluralism Project

Situating Buddhism in its Social and Historical Context

This lesson introduced a few people and events that are significant to Buddhist history. It describe the historical relationship between Buddhist and non-Buddhist communities, and it explained how significant people and events in Buddhist history contribute to Buddhist identity, culture and religious practice today. To learn more about the history of Buddhism in greater detail, watch the TedEd video below.

References & Resources

- Buddhism in the World: Timeline, the Pluralism Project

- Buddhism: An Introduction, PBS.

- Buddhism, Ancient History Encyclopedia.

- Buddhism: An Introduction, BBC.

- The History of Buddha, History Cooperative.

- Religions: Buddhism, BBC.

- Cultural Syncretism in Central Asia, Khan Academy

- Buddhism and the Beats, Oxford Bibliographies

- Buddhism and Buddhism in China

- Seven Wonders of the Buddhist World, BBC documentary

For Discussion: Research and describe an historically significant person or event in Buddhist history. 1. Describe person or event, 2.) explain scholarly evidence of person or event, 3.) Describe how this person or event is significant in Buddhist memory. Include references, and always respond to other student posts in discussion.

When you complete the discussion, move on to the Dharma lesson.