In Buddhism, dharma means “cosmic law and order”, and the term is also applied to the teachings of Buddha. Through several centuries following the death of the first Buddha, scripture and doctrine developed in several closely related literary languages of ancient India, especially in Pali and Sanskrit. This lesson will introduce important Buddhist texts, address significant stories, events and teachings in the Buddhist texts, and explore the messages and meanings communicated in Buddhist texts.

Objectives:

- describe important Buddhist texts

- recognize significant stories, events and teachings in the Buddhist texts

- interpret the messages and meanings communicated in Buddhist texts.

More than one text

The teachings attributed to the Buddha were transmitted orally by monks, prefaced by the phrase “evam me sutam” (“thus have I heard”). Therefore, it is difficult determine the extent that the discourses were preserved as they were spoken. Through several centuries following the death of the first Buddha, scripture and doctrine developed in several closely related literary languages of ancient India, especially in Pali and Sanskrit, as well as various Indo-Aryan languages which were then translated into other local languages as Buddhism spread. Buddhist traditions have generally divided these texts with unique categories and divisions, such as that between buddhavacana “word of the Buddha,” many of which are known as “sutras,” and other texts, such as shastras (treatises) or Abhidharma.

Theravada

The Tipitaka (Pali ti, “three,” + pitaka, “baskets” also ‘tripitaka’) is the collection of primary Pali language texts which form the doctrinal foundation of Theravada Buddhism. They are thought to be the earliest collection of Buddhist writings, and together with several commentaries and chronicles constitute the complete body of classical Theravada texts.

Vinaya Pitaka is the first division of the Tipitaka, and it provides a textual framework upon which the monastic community (Sangha) is built. It includes not only the rules governing the life of every Theravada bhikkhu (monk) and bhikkhuni (nun), but also a host of procedures and conventions of etiquette that support harmonious relations, both among the monastics themselves, and between the monastics and their lay supporters, upon whom they depend for all their material needs. to learn more about the Vinaya Pitaka, explore the English translations on this Access to Insight webpage.

The collection of Sutras, or discourses, are attributed to the Buddha and a few of his closest disciples. They contain all the central teachings of Theravada Buddhism. The sutras are divided among five nikayas (collections):

- Digha Nikaya — the “long collection”

- Majjhima Nikaya — the “middle-length collection”

- Samyutta Nikaya — the “grouped collection”

- Anguttara Nikaya — the “further-factored collection”

- Khuddaka Nikaya — the “collection of little texts”:

Abhidhamma Pitaka is a collection of seven texts in which the underlying doctrinal principles presented in the Sutra Pitaka are reworked and reorganized into a systematic framework that can be applied to an investigation into the nature of mind and matter. It provides a detailed analysis of the basic natural principles that govern mental and physical processes. Whereas the Sutta and Vinaya Pitakas lay out the practical aspects of the Buddhist path to Awakening, the Abhidhamma Pitaka provides a theoretical framework to explain the causal underpinnings of that very path. In Abhidhamma philosophy the familiar psycho-physical universe (our world of “trees” and “rocks,” “I” and “you”) is distilled to its essence: an intricate web of impersonal phenomena and processes unfolding at an inconceivably rapid pace from moment to moment, according to precisely defined natural laws.

Watch the video below to learn more about the tripitaka.

Mahayana

There are more than 2,000 Mahayana sutras, which are sacred teachings embraced mainly by Mahayana Buddhists. They constitute a very broad genre of Buddhist scriptures of which the Mahayana Buddhist tradition claim are original teachings of the Buddha. (The Theravada and the other Early Buddhist Schools claim that the Mahayana Sutras are later compositions, not taught by the Buddha.) The idea of the bodhisattva, one who seeks to become a Buddha, is central to Mahayana ideology. In contrast to the dominant thinking in non-Mahayana Buddhism, which limits the designation of bodhisattva to the Buddha before his awakening (bodhi), or enlightenment, Mahayana teaches that anyone can aspire to achieve awakening (bodhicittot-pada) and thereby become a bodhisattva. For Mahayana Buddhism, awakening consists in understanding the true nature of reality. While non-Mahayana doctrine emphasizes the absence of the self in persons, Mahayana thought extends this idea to all things. The radical extension of the common Buddhist doctrine of “dependent arisal” (pratityasamutpada), the idea that nothing has an essence and that the existence of each thing is dependent on the existence of other things, is referred to as emptiness (shunyata).

The Lotus Sutra is probably the most significant of the Mahayana Sutras. It describes a sermon delivered by the Buddha to an assembly of buddhas, boddhisatvas, and other celestial beings. This sermon emphasizes the importance of becoming a boddhisatva, realizing one’s buddha-nature, and other Mahayana concepts. The Lotus Sutra is revered by most Buddhists, and is the primary focus of the Nichiren school. To learn more about the Lotus Sutra, watch the video lecture below.

The Heart Sutra is another important Mahayana text. It is very short, only a few pages, and provides a concise summary of key Mahayana concepts. Presented as the teachings the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, the Heart Sutra describes the five skandhas (elements of human nature), as well as the Mahayana views of “emptiness,” nirvana, and ultimate reality. to listen to Heart Sutra in chant, watch the video below.

The Land of Bliss Sutra is especially important in Pure Land Buddhism. It tells the story of Amitabha (Amida) Buddha’s vow to help people reach nirvana, describes the Pure Land, and relates what one must do to be reborn in the Pure Land. The video below provides an animated version,

Vajrayana

The Vajrayana Tibetan Buddhist canon is a loosely defined list of sacred texts recognized by various schools of Tibetan Buddhism. In addition to foundational Buddhist texts from early Buddhist schools and Mahayana texts, they also include the Kangyur or Kanjur (‘The Translation of the Word’) and the Tengyur or Tanjur (Tengyur) (‘Translation of Treatises’).

Kangyur (tantric) or “Translated Words” consists of works in about 108 volumes believed to have been spoken by the Buddha himself. All texts presumably had a Sanskrit original, although in many cases the Tibetan text was translated from Chinese or other languages.

Tengyur or “Translated Treatises” is commentaries, treatises and abhidharma works (both Mahayana and non-Mahayana). The Tengyur contains around 3,626 texts in 224 Volumes.

Bardo Thodol, also known as ‘The Tibetan Book of the Dead’, (Tibetan: “Liberation in the Intermediate State Through Hearing”) is a funerary text that is recited to ease the consciousness of a recently deceased person through death and assist it into a favorable rebirth. A central tenet of all schools of Buddhism is that attachment to and craving for worldly things spurs suffering and unease (dukkha), which influence actions whose accumulated effects, or karma, bind individuals to the process of death and rebirth (samsara). Those who have attained enlightenment (bodhi) are thereby released from this process, attaining liberation (moksha). Those who remain unenlightened are drawn by karma, whether good or bad, into a new life in one of six modes of existence: as a sufferer in hell (enduring horrible torture), as a wandering ghost (driven by insatiable craving), as an animal (ruled by instinct), as a demigod (lustful for power), as a human being (balanced in instinct and reason), or as a god (deluded by their long lives into believing they are immortal).

The Vajrayana (Tantric) Buddhism that emerged in Central Asia and particularly in Tibet developed the concept of the bardos, the intermediate or transitional states that mark an individual’s life from birth to death and rebirth. The period between death and rebirth lasts 49 days and involves three bardos. The first is the moment of death itself. The consciousness of the newly deceased becomes aware of and accepts the fact that it has recently died, and it reflects upon its past life. In the second bardo, it encounters frightening apparitions. Without an understanding that these apparitions are unreal, the consciousness becomes confused and, depending upon its karma, may be drawn into a rebirth that impedes its liberation. The third bardo is the transition into a new body.

For a brief overview of Bardo thodol, watch the video below.

Common Themes in Buddhist Belief and Practice

The vast body of Buddhists texts provides a wide range of interpretations and concepts among the different Buddhist traditions. Yet, most traditions share central themes such as the Four Noble Truths as guiding principles, the Noble Eightfold Path for liberation, and key concepts such as karma,

Four Noble Truths

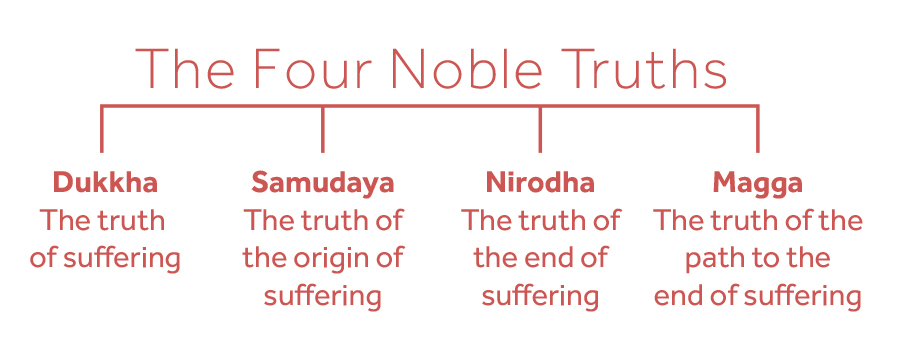

Awareness of the fundamental realities of led the Buddha to formulate the Four Noble Truths:

- the truth of misery (dukkha; literally “suffering” but connoting “uneasiness” or “dissatisfaction”),

- the truth that misery originates within the craving for pleasure and for being or nonbeing (samudaya),

- the truth that this craving can be eliminated (nirodhu),

- the truth that this elimination is the result of following a methodical way or path (magga).

To learn more about the Four Noble Truths, watch the video below and/or watch a more in-depth lecture by the Dali Lama at www.dalailama.com

Law of Dependent Origination

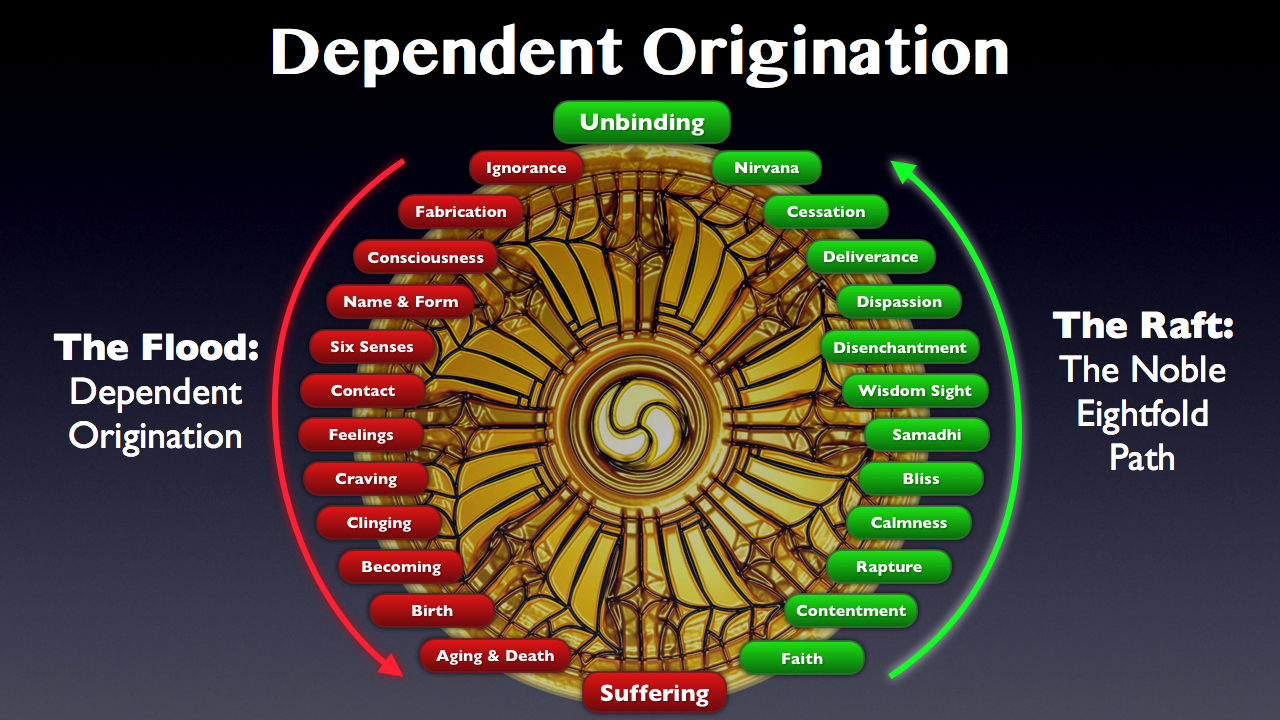

The Buddha, according to the early texts, also discovered the law of dependent origination (paticca-samuppada), whereby one condition arises out of another, which in turn arises out of prior conditions. Every mode of being presupposes another immediately preceding mode from which the subsequent mode derives, in a chain of causes. According to the classical rendering, the 12 links in the chain are: ignorance (avijja), karmic predispositions (sankharas), consciousness (vinnana), form and body (nama-rupa), the five sense organs and the mind (salayatana), contact (phassa), feeling-response (vedana), craving (tanha), grasping for an object (upadana), action toward life (bhava), birth (jati), and old age and death (jaramarana). According to this law, the misery that is bound with sensate existence is accounted for by a methodical chain of causation. Despite a diversity of interpretations, the law of dependent origination of the various aspects of becoming remains fundamentally the same in all schools of Buddhism. to learn more, watch the video below.

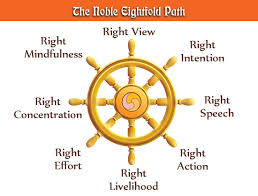

Eight Fold Path

The law of dependent origination, however, raises the question of how one may escape the continually renewed cycle of birth, suffering, and death. It is not enough to know that misery pervades all existence and to know the way in which life evolves; there must also be a means to overcome this process. The means to this end is found in the Eightfold Path, which is constituted by right views, right aspirations, right speech, right conduct, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right meditational attainment. To learn more, watch the video below.

Karma

The belief in rebirth, or samsara, as a potentially endless series of worldly existences in which every being is caught up was already associated with the doctrine of karma (Sanskrit: karman; literally “act” or “deed”) in pre-Buddhist India, and it was accepted by virtually all Buddhist traditions. According to the doctrine, good conduct brings a pleasant and happy result and creates a tendency toward similar good acts, while bad conduct brings an evil result and creates a tendency toward similar evil acts. Some karmic acts bear fruit in the same life in which they are committed, others in the immediately succeeding one, and others in future lives that are more remote. This furnishes the basic context for the moral life.

The acceptance by Buddhists of the teachings of karma and rebirth and the concept of the no-self gives rise to a difficult problem: how can rebirth take place without a permanent subject to be reborn? Indian non-Buddhist philosophers attacked this point in Buddhist thought, and many modern scholars have also considered it to be an insoluble problem. The relation between existences in rebirth has been explained by the analogy of fire, which maintains itself unchanged in appearance and yet is different in every moment—what may be called the continuity of an ever-changing identity.

Among these theories is the belief that the universe is the product of karma, the law of the cause and effect of actions. The beings of the universe are reborn without beginning in six realms as gods, demigods, humans, animals, ghosts, and hell beings. The cycle of rebirth, called samsara(literally “wandering”), is regarded as a domain of suffering, and the Buddhist’s ultimate goal is to escape from that suffering. The means of escape remains unknown until, over the course of millions of lifetimes, a person perfects himself, ultimately gaining the power to discover the path out of samsara and then revealing that path to the world.

To learn more about karma, watch this video by Hans Wilhelm.

Nirvana

The aim of Buddhist practice is to be rid of the delusion of ego and thus free oneself from the fetters of this mundane world. One who is successful in doing so is said to have overcome the round of rebirths and to have achieved enlightenment. This is the final goal in most Buddhist traditions, though in some cases (particularly though not exclusively in some Pure Land schools in China and Japan) the attainment of an ultimate paradise or a heavenly abode is not clearly distinguished from the attainment of release.

The living process is again likened to a fire. Its remedy is the extinction of the fire of illusion, passions, and cravings. The Buddha, the Enlightened One, is one who is no longer kindled or inflamed. Many poetic terms are used to describe the state of the enlightened human being—the harbor of refuge, the cool cave, the place of bliss, the farther shore. The term that has become famous in the West is nirvana, translated as passing away or dying out—that is, the dying out in the heart of the fierce fires of lust, anger, and delusion. But nirvana is not extinction, and indeed the craving for annihilation or nonexistence was expressly repudiated by the Buddha. Buddhists search for salvation, not just nonbeing. Although nirvana is often presented negatively as “release from suffering,” it is more accurate to describe it in a more positive fashion: as an ultimate goal to be sought and cherished.

To learn more about Nirvana, watch the video below.

Sacred Sites

Sites associated with the Buddha’s life became important pilgrimage places, and regions that Buddhism entered long after his death—such as Sri Lanka, Kashmir, and Burma (now Myanmar)—added narratives of his magical visitations to accounts of his life. Today, many of these sites receive Buddhist pilgrims from around the world. the short video below provides a synopsis of four holiest Buddhist sites in India and Nepal:

- Lumbini – where Buddha was born

- Bodhgaya – where Buddha attained enlightenment

- Sarnath – where Buddha taught

- Kushinagar – where Buddha died

Interpreting Messages and Meanings in Buddhism

This lesson introduced important Buddhist texts in Theravada, Mahayana and Tibetan Buddist traditions. It addressed significant stories, events and teachings in a few of the Buddhist texts, and it explored a variety of messages and meanings communicated in Buddhist texts.

References & Resources

- Buddhist Scriptures, Georgetown University Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, & World Affairs.

- Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge

- The Buddhist Experience, the Pluralism Project

- Buddhist Digital Resource Center

- Buddha Dharma Education Association

For discussion: Select one of the elements presented in this lesson; a sutra, belief, story or ritual, or philosophy in Buddhism. Research one additional scholarly article about the element. Using the theoretical frameworks presented in the Introductory module in this course, interpret the messages and meanings conveyed by the element you selected using the format below;

- Introduction: Introduce the element and make a declarative thesis statement using a specific theoretical perspective.

- Body: Interpret the element from that perspective; what are the messages and meanings? What role does it play and why?

- Conclusion: Tie your thesis back to what was presented in the body.

- References: Cite the additional article in a proper format

(min 500 words) Be prepared to discuss the story, law or ritual in class.

When you complete the discussion, move on to the Global Buddhism lesson.