Haiku is a short form of poetry that originated in Japan. Traditionally, haikus evoke images from nature that emphasizes simplicity, intensity, direct expression and a commentary about life. Haiga is a style of painting that incorporates the elements of haiku. This lesson will provide a brief overview of haiku and haiga.

Lesson Objectives

- define and describe haiku and haiga

- analyze a haiku using elements of poetry

- produce a haiku and haiga

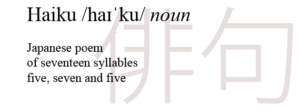

Haiku is an unrhymed poetic style consisting of 17 syllables arranged in three lines of 5, 7, and 5 syllables respectively. Haiku first emerged in Japanese literature during the 17th century, as a reaction to renga an elaborate and symbolic poetic style that often consisted of at least 100 stanza. The hokku was a three-line stanza in the renga that set the tone with subjects such as the season, time of day, and the dominant features of the landscape. The hokku became an independent poem known as the haiku in the 19th century. Today the term haiku is used to describe all poems that use the three-line 17-syllable structure and the haiku elements.

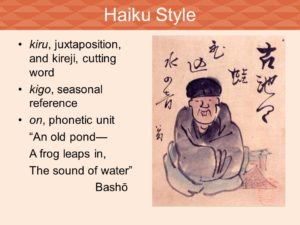

In contrast to the highly symbolic and lengthy renga, haiku is simple and direct with deeper meanings embedded in the imagery it evokes. Haiku was traditionally written in the present tense and focused on associations between images. There was a pause at the end of the first or second line, and a “season word,” or kigo, specified the time of year. As the form has evolved, many of these rules—including the 5/7/5 practice—have been routinely broken. However, the general philosophy of haiku has been preserved in the elements:

- the focus on a brief moment in time;

- a use of provocative, colorful images;

- an ability to be read in one breath; and

- a sense of sudden enlightenment and illumination.

For example, seventeenth century poet, Matsuo Basho, wrote this classic haiku:

An old pond!

A frog jumps in—

the sound of water.

The brief moment in time is expressed with the frog’s jump,’ and the activity of a frog provides the kigo, a seasonal reference, to summer or spring. We can find the kiru, juxtaposition, with the water which was once still and then disrupted by the frog as well as the contrast between ancientness of an old still pond and the youthful activity of a frog’s jump. As a whole, Basho’s haiku illuminates greater meanings such as the relationship between old and new, activity and stillness, and the profoundness of everyday mundane events.

The observant, simple and direct ‘less is more’ style of Basho’s haiku reflects Zen Buddhism which is centered on achieving moments of enlightenment through meditation. Through practice, meditation stills the hectic activity of the mind (planning, speculating, fantasising, hoping, dreading, etc.) and leads to a calmer, more simple mental space. In the calm space, the mind experiences awareness, truth, love, silence, observance, and stillness. In Zen Buddhism, great enlightenment called satori is sought through many years of disciplined meditation. Yet, kensho refers to little flashes of enlightenment through intense forms of everyday noticings that seem to reveal a truth or connect us with the sense of awe. Similarly, haiku is a momentary, condensed poetic form that gives the reader kensho insight. According to George Marsh, ‘It is this that is the essence of haiku, not its number of syllables.’

Basho is among the greatest traditional haiku poets. He traveled throughout Japan and produced haikus based on his experiences. The simplicity of the haiku style and the familiarity of the subject matter made his haikus accessible to a a diverse population in Japanese society. The popularity of haiku expanded beyond Japan after World War II, and today haiku are written in a wide range of languages. English haiku were especially influential during the early 20th century Britain and the United States. Modern English-language haiku poets include Robert Hass, Paul Muldoon, Jack Kerouac and many others. Anselm Hollo, whose poem “5 & 7 & 5” reflects contemporary imagery;

round lumps of cells grow

up to love porridge later

become The Supremes

Haiku philosophy influenced poet Ezra Pound, who noted the power of haiku’s brevity and juxtaposed images. He wrote, “The image itself is speech. The image is the word beyond formulated language.” The influence of haiku on Pound is most evident in his poem “In a Station of the Metro,” which began as a thirty-line poem, but was eventually pared down to two:

The apparition of these faces in the crowd;

Petals on a wet, black bough.

There are several other forms of poetry related to haiku, such as senryū and tanka, as well as other art forms that incorporate haiku, such as haibun and haiga.

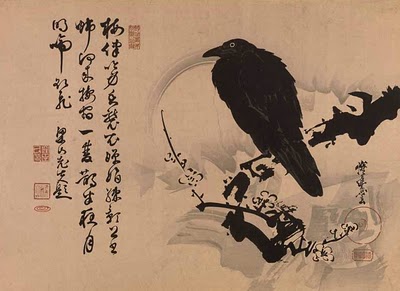

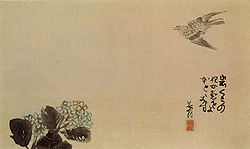

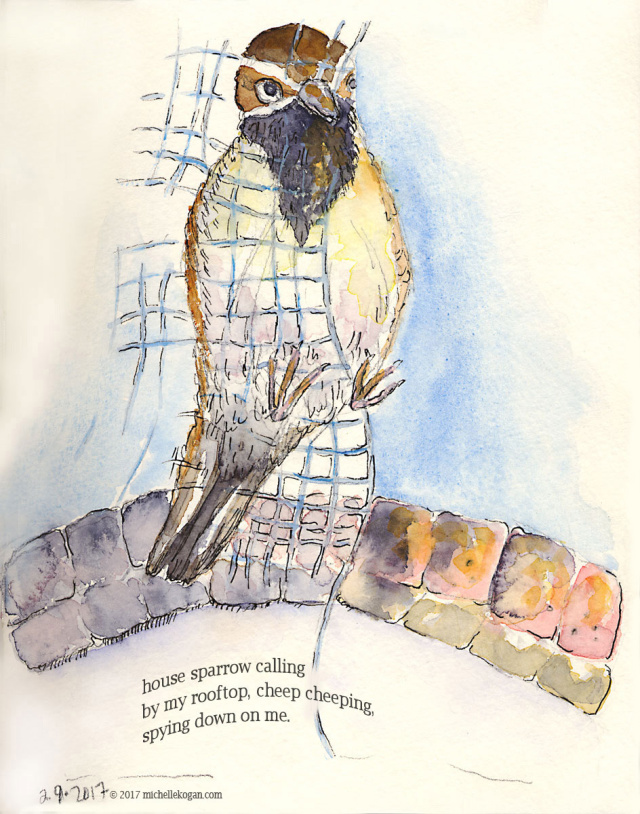

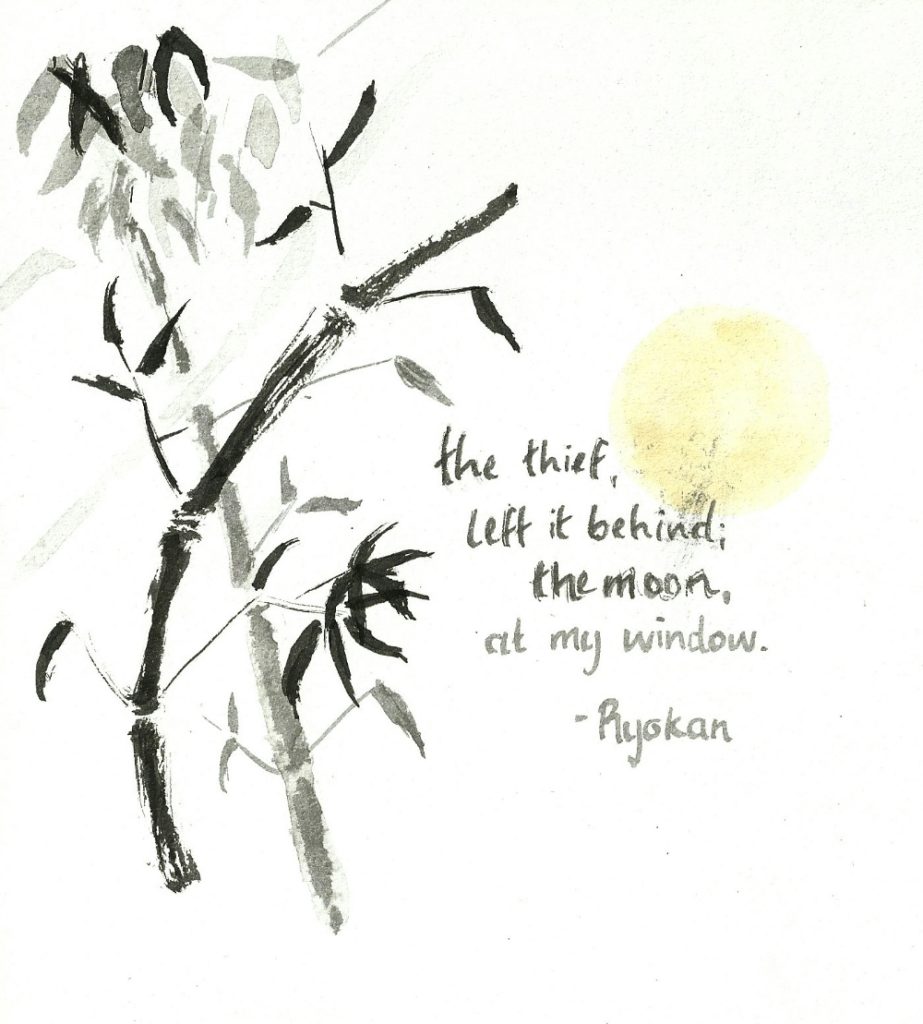

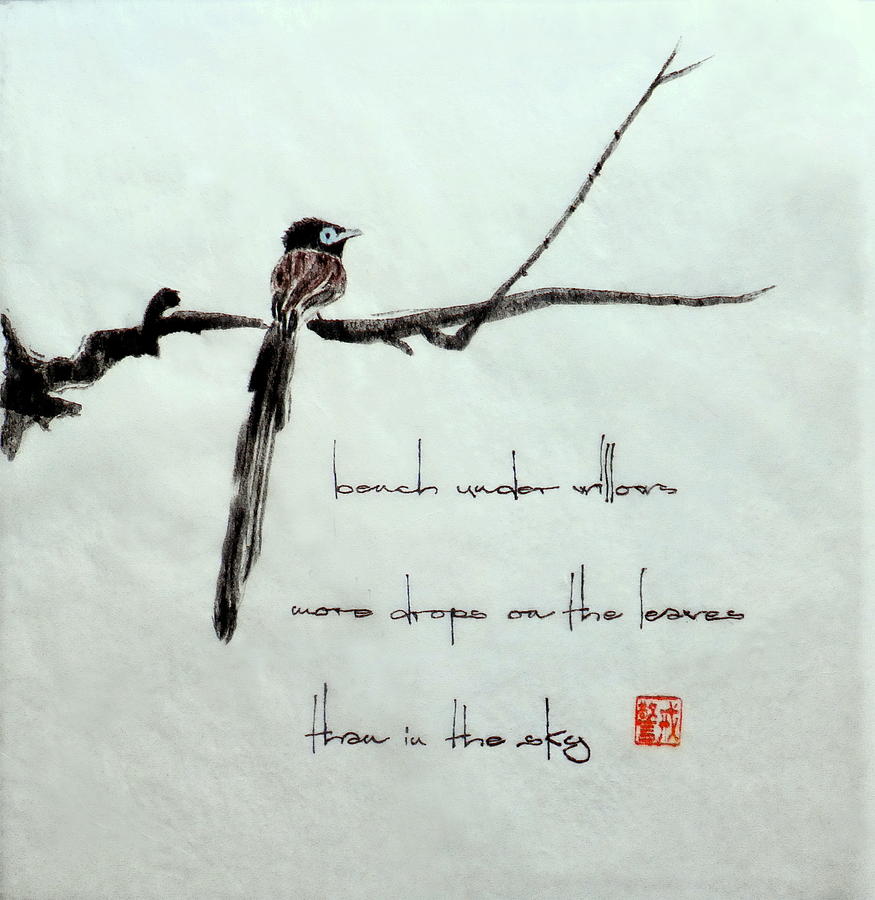

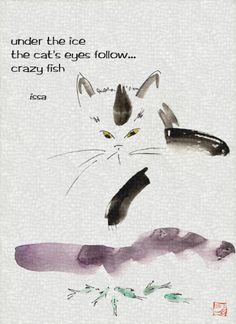

Haiga Drawing

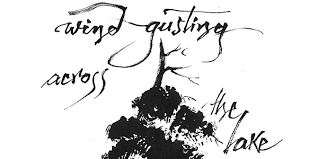

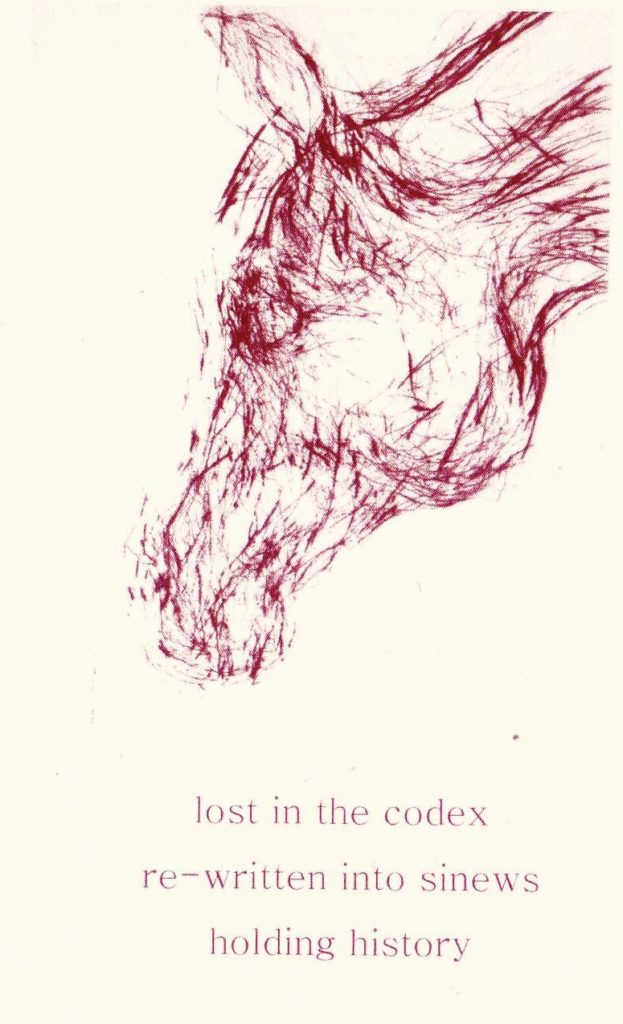

Haiga drawing is a style of Japanese painting that incorporates the aesthetics of haikai. Haiga are typically painted by haiku poets (haijin), and often accompanied by a haiku poem. Like the poetic form it accompanied, haiga was based on simple, yet often profound, observations of the everyday world. Stephen Addiss points out that “since they are both created with the same brush and ink, adding an image to a haiku poem was … a natural activity.”

Stylistically, haiga vary widely based on the preferences and training of the individual painter, but generally show influences of formal Kanō school painting, minimalist Zen painting, and Ōtsu-e, while sharing much of the aesthetic attitudes of the nanga tradition. Some were reproduced as woodblock prints. The subjects painted likewise vary widely, but are generally elements mentioned in the calligraphy, or poetic images which add meaning or depth to that expressed by the poem. The moon is a common subject in these poems and paintings, sometimes represented by the Zen circle ensō, which evokes a number of other meanings, including that of the void. Other subjects, ranging from Mount Fuji to rooftops, are frequently represented with a minimum of brushstrokes, thus evoking elegance and beauty in simplicity.

Examples of Haiga with Haiku

Analyzing Haikus

Haiku communicate deep and profound meanings in few words. Unlike long wordy poems, haikus rely on implicit meanings rather than explicit statements to communicate a mood, message, or illumination. Analyzing the elements of a haiku can help identify the implicit meanings in a haiku.

- What is the name and date of the poet? What does this tell you about the context of the haiki?

- What style is the Haiku? (traditional 5-7-5 or free verse)

- What is the Kiru (juxtaposition)?

- What is the Kireji (cutting word)?

- What is the kigo (seasonal reference) or temporal reference?

- What is the overall moment or meaning of the haiku?

Haikus in the Humanities

The haiku tradition reflects the dynamic nature of poetic connections as a culturally specific form of simplistic Japanese poetry that emerges from a complex style and is appropriated through time and across cultures in ways that connect people to nature, life and each other.

References & Resources

To learn more about haiku and haiga, explore the links below.

- Biley and Smith. 2003. “Attempting to say something without saying it: writing haiku in healthcare education,” Medical Humanities Volume 29 Issue 1

- Higginson, W. J. (2008). The Haiku Seasons: Poetry of the Natural World. United States: Stone Bridge Press.

- Shirane, Haruo. Beyond the Haiku Moment

- K. Yamamoto, Y. Isomoto, Y. Yamada, J. Emrich, Y. Takeda and M. Ohashi, “Intercultural web communication with haiku and haiga between America and Japan through the Internet,” International Conference on Computers in Education, 2002. Proceedings., Auckland, New Zealand, 2002, pp. 1203-1204 vol.2,

- ‘Haiku and Zen’ New Zealand Poetry Society.

- Marsh, George. Haiku and Zen. The Haiku Foundation.

For Discussion in Canvas

Select a haiku (either traditional 5-7-5 or one that breaks the rules) and produce a brief (approximate 50-100 words) analysis. Use the elements of haiku analysis introduced in the lesson to break apart and pull the haiku back together with your conclusion, and place them in bold or italics to show you used them. Be sure to research the poet and include details about their life to help establish social and historical context. Copy the haiku into the body of your discussion (it does not count toward the one-page analysis). Be sure to read and respond to the haikus and analysis contributed by your classmates.

For Journal Expression

Write a haiku and draw or paint a haiga to accompany your haiku. Embed a jpg of your haiku/haiga with a brief (approx. 50-word) explanation of the elements of your haiku; kiru, kireji, kigo, etc. What is the awareness, enlightenment or illumination you want to give to the reader? Be sure to meet the criteria and respond to at least two other student haiku/haiga. The Ted talk below explains the process (and benefits) of daily haiku writing.

For Extra Credit

Similar to Haiku and Haiga, many meditation practices employ a technique or series of techniques that emphasize simplicity, intensity, directness of expression, and commentary about life in order to alter cognitive and/or emotional states and conditions in an effort to improve well being. Learn more and earn extra credit by participating in a brief meditation of your choice, visit the Meditation page.